Virus has been ‘very devastating’ for many African airlines

KAMPALA, Uganda — A “new baby” was born with the revival of Uganda Airlines, the country’s president announced last year. But now its four new jets sit idle, business suspended indefinitely because of coronavirus-related travel restrictions.

Questions are swirling in Africa and elsewhere over the financial wisdom of sustaining prestige carriers that often have a tiny share of an aviation market that sees no recovery in sight.

African airlines had been piling on debt long before the pandemic but government bailouts allowed them to limp on for years. Now, as sub-Saharan Africa faces its first recession in a quarter-century, some airlines will find it harder to survive. That’s despite growing global interest in the continent of 1.3 billion people.

In some cases, local airlines are so important for pan-African business on a vast continent with historically poor infrastructure that their collapse would cripple speedy travel. In other cases, however, airlines have been seen as vanity projects for states that can hardly afford to support them.

Nowel Ngala, commercial director of Asky Airlines — a carrier launched in 2010 by a group of regional banks hoping to solve transport difficulties in central and West Africa — said the pandemic has been “very devastating “ to the company, whose nine aircraft are grounded. Revenue losses are substantial and there have been “serious impacts in terms of maintaining” the planes for whenever business resumes.

The International Air Transport Association in April warned that African airlines could lose $6 billion in passenger revenue compared to last year, and half of the region’s 6 million jobs in aviation and related industries could be lost. Air traffic this year is expected to fall by half, it said.

“These estimates are based on a scenario of severe travel restrictions lasting for three months, with a gradual lifting of restrictions in domestic markets, followed by regional and intercontinental,” the IATA said.

That three-month period is already nearing an end, with no return to normal air travel in sight.

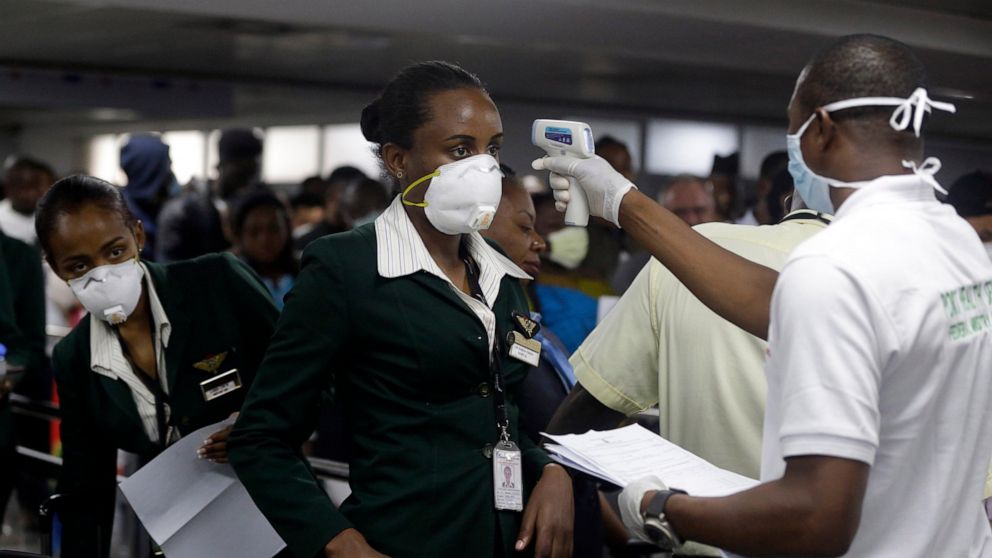

Even Ethiopian Airlines, Africa’s only profitable airline in recent years, has signaled distress, citing revenue losses of up to $550 million between January and April. As a survival measure, the airline has thrown itself into cargo operations, including shipping medical supplies across Africa and to other continents.

“Some 22 of our passenger aircraft have been converted to cargo,” CEO Tewolde Gebremariam told The Associated Press. “Once the pandemic is brought under control and passenger flights resume, we will configure them back into their original passenger cabin configurations.”

If the crisis lingers, he said, “we will discuss with our owner, the Ethiopian government, on how to manage the situation going forward, and we may also discuss with our creditor banks for liquidity loans.”

Addis Ababa, Ethiopia’s capital, has become Africa’s gateway to Gulf nations and beyond. Now it is a key hub for shipping humanitarian supplies during the pandemic.

Another major African airline, South African Airways, hasn’t been profitable since 2011 and has been under bankruptcy protection since December. Tired of issuing bailouts, the government is demanding a new business plan.

“We are now faced with the unknown post the COVID-19 pandemic and there is no precedent or certainty which can be followed in developing a new strategy,” the department of public enterprises announced on May 1, saying the airline will be restructured. Administrators aim to lay off nearly 5,000 employees to keep the airline afloat.

“Airlines that were struggling before the pandemic will likely end up filing for bankruptcy or seek bailouts,” the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa has warned, calling air transport a critical sector for the continent’s economy, along with tourism, as global ties and investment have grown.

The revived Uganda Airlines barely had the chance to get started.

Without solid support from the state while grappling with how to comply with new safety guidelines, Uganda Airlines “may as well go home,” said Francis Babu, a pilot and former government minister. The airline’s CEO and spokesman did not respond to requests for comment.

In neighboring Kenya, Kenya Airways CEO Allan Kilavuka has been blunt.

“Even before this crisis we were not in a good place,” he told the Metropol television channel on May 6. The airline’s business model and market approach will need to change, he said. But asked how he sees Kenya Airways coping after the pandemic, he replied: “No one knows.”

Employees have taken pay cuts of up to 80% as Kenya Airways undergoes a re-nationalization process started last year to help it return to profitability. In February the airline received a government loan of nearly $5 million to overhaul its fleet’s engines.

A further cash infusion from the state is needed, Kilavuka said, “anything that you can afford.”

The company’s growing debt is one reason that Aly-Khan Satchu, a financial analyst based in Nairobi, believes that authorities will need to create another version of Kenya’s flag carrier “with a clean balance sheet.”

Kenya Airways, which depends on passenger traffic for 90% of its revenue, will have to pivot to cargo and reduce its network to create an agile state carrier, he said. “I appreciate it serves a national interest function but the balance sheet has now crossed a tipping point.”

In Rwanda, the government said it will increase its funding to national carrier RwandAir, whose cost-trimming includes pay cuts of up to 65% and the suspension of contracts with some pilots and non-essential staff until further notice.

Times are even harder for Air Zimbabwe, the one-plane national carrier of the southern African nation, saddled with debt of more than $300 million even before the pandemic. The airline said in April it was forcing dozens of employees into unpaid leave until the Boeing 767 can fly passengers again.

———

Elias Meseret in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, Ignatius Ssuuna in Kigali, Rwanda, Farai Mutsaka in Harare, Zimbabwe, and Erick Kaglan in Lomé, Togo, contributed.

![]()