In poor regions, easing virus lockdowns brings new risks

SAO PAULO — As many countries gingerly start lifting their lockdown measures, experts worry that a further surge of the coronavirus in under-developed regions with shaky health systems could undermine efforts to halt the pandemic, and they say more realistic options are needed.

Brazil, Mexico, South Africa, India and Pakistan are among countries easing tight restrictions, not only before their outbreaks have peaked but also before any detailed surveillance and testing system is in place to keep the virus under control. That could ultimately have devastating consequences, health experts warn.

“Politicians may be desperate to get their economies going again, but that could be at the expense of having huge numbers of people die,” said Dr. Bharat Pankhania, an infectious diseases expert at the University of Exeter in Britain.

He said re-imposing recently lifted lockdown measures was equally dangerous.

“Doing that is extremely worrying because then you will build up a highly resentful and angry population, and it’s unknown how they will react,” Pankhania said. And as nearly every developed country struggles with its own outbreak, there may be fewer resources to help those with long overstretched capacities.

Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, director-general of the World Health Organization, said Monday the pandemic was “worsening” globally, noting that countries on Sunday reported the biggest-ever one-day total: more than 136,000 cases. Among those, nearly 75% of the cases were from 10 countries in the Americas and South Asia.

Wealthy countries in Europe and North America hit first by the pandemic are training armies of contact tracers to hunt down cases, designing tracking apps and planning virus-free air travel corridors.

But in many poor regions where crowded slums and streets mean even basic measures like hand-washing and social distancing are difficult, the coronavirus is exploding now that restrictions are being removed. Last week, Brazil, Mexico, South Africa, India and Pakistan all saw one-day records of new infections or deaths as they reopened public spaces and businesses.

Clare Wenham of the London School of Economics described the situation in Brazil as “terrifying,” noting the government’s decision to stop publishing a running total of COVID-19 cases and deaths.

“We’ve seen problems with countries reporting data all over the world, but to not even report data at all is clearly a political decision,” she said. That could complicate efforts to understand how the virus is spreading in the region and how it’s affecting the Brazilian population, Wenham said.

Johns Hopkins University numbers showed Brazil recorded more than 36,000 coronavirus deaths Monday, the third-highest in the world, just ahead of Italy. There were nearly 692,000 cases, putting it second behind the U.S.

Rio de Janeiro allowed surfers and swimmers back in the water and small numbers of beach-goers were defying a still-active ban on gathering on the sand.

Relaxing restrictions “is dangerous because we’re still at the peak, right? So it’s a little dangerous,” said Alessandra Barros, a 46-year-old cashier on the sidewalk next to Ipanema beach. “Today it’s calm, but this weekend will be crowded.”

Bolivia has authorized reopening most of the country, Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro also recently unwound restrictions, Ecuador’s airports have resumed flights and shoppers have returned to some of Colombia’s malls.

In Mexico, President Andrés Manuel López Obrador urged the country to stay calm after officials last week reported escalating fatalities that rivaled those in Brazil or the U.S.

“Let there not be psychosis, let there not be fear,” López Obrador said, while accusing the media of fanning concerns of an escalating crisis.

Across Latin America, countries that cracked down early and hard, like El Salvador and Panama, have done relatively well, although some of that has come at the expense of human rights and civil liberties, Wenham said.

“Countries willing to take the short-term hit are the ones coming out better,” she said, adding that poor countries weren’t entirely without options, noting early, pre-emptive actions by Sierra Leone and Liberia.

“They learned from the Ebola outbreak and moved quickly when they decided their economy couldn’t cope with community transmission,” she said. So far, numbers have been relatively low in both West African countries.

Dr. Nathalie MacDermott, a clinical lecturer at King’s College London, warned that some countries might be lulled into a false sense of security, citing South Africa as an example.

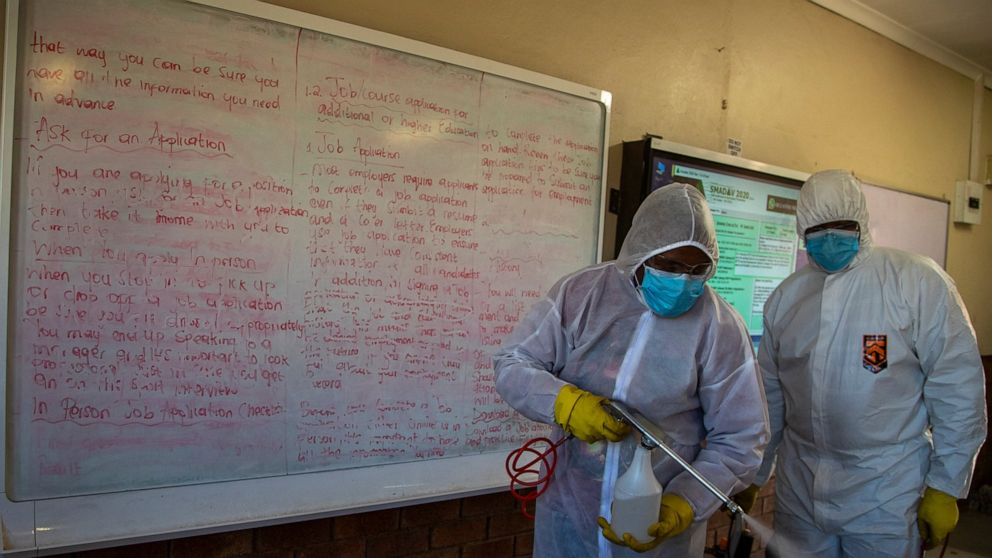

“Their response looked quite promising initially, but it seems premature to release the lockdown without a better level of testing in place,” she said.

South Africa’s cases are “rising fast,” according to President Cyril Ramaphosa. More than half of its approximately 48,000 confirmed cases have been recorded in the last two weeks, prompting concerns that Africa’s most developed economy could see a steep rise in infections shortly after restrictions are relaxed.

MacDermott said the surge of COVID-19 in many developing countries suggests “we will potentially struggle more to get on top of it,” and that the virus might persist long after developed countries bring it under control.

“That could result in very stringent travel measures on those parts of the world where the virus is still circulating,” she said.

In Pakistan, the number of infections continued to rise as Prime Minister Imran Khan said the country’s poorest cannot survive a strict lockdown after easing restrictions last month.

After refusing to close mosques and opening up the country even as medical experts pleaded for stricter measures, Pakistan’s caseload soared Monday to 103,671, with 2,067 deaths. Still, authorities shut down thousands of shops and markets nationwide last week in raids of those violating social distancing regulations.

Some experts say lockdowns were always “panic measures” and not designed to be sustainable, particularly in developing countries.

“The strategy has its roots in China, in the desire to eliminate the disease, but that clearly went out the window a couple of months ago,” said Mark Woolhouse, a professor of infectious disease epidemiology at the University of Edinburgh.

“Many countries are now deciding that the cure could turn out to be worse than the disease,” he said. Woolhouse suggested that countries unable to lock down their populations could focus instead on targeted interventions to protect those most at risk, such as people over 60 or those with underlying medical conditions.

“Countries are simply not following World Health Organization advice to lock down and are saying they need another strategy,” Woolhouse said. He noted the relatively younger demographics of many developing countries might help them avoid the high death rates seen in Italy, Spain and Britain.

Even tiny Panama, once Latin America’s fastest-growing economy, is struggling to maintain some of the region’s tightest controls amid simultaneous economic slowdown and disease spread.

“It’s impossible to maintain a quarantine for all of 2020,”‘ said Dr. Xavier Sáenz-Llorens, a government adviser on the disease response. “The country would sink.”

—-

Cheng reported from London. Contributing were David McHugh in Frankfurt, Germany, Suzan Fraser in Ankara, Turkey, Cara Anna and Andrew Meldrum in Johannesburg, Munir Ahmed and Kathy Gannon in Islamabad, Christopher Sherman in Mexico City, David Biller in Rio de Janeiro and Juan Zamorano in Panama City.

———

Follow AP coverage of the pandemic at https://apnews.com/VirusOutbreak and https://apnews.com/UnderstandingtheOutbreak

![]()