These kids have been in day care this whole time and may hold solutions for schools

The four-story brick building, known as PS/IS 128 in Queens, New York, has been repurposed into what is known as a “Regional Enrichment Center” — one of a number of child care centers throughout the state that has remained open during the coronavirus pandemic for the children of parents who cannot work from home and are considered “essential” workers.

Starting with only 16 children when the coronavirus forced schools to close in March, PS/1S 128 now welcomes more than 130 children per day ranging from 3-year-olds to 10th-graders. And despite operating at the height of Covid-19 outbreaks in New York, there hasn’t been a single reported case of coronavirus at the REC.

But those such as Ramage, who run child care centers on the ground, say taking the REC model to national scale could prove more challenging than it appears at first glance.

Temperature checks, masks and a giant sea turtle

CNN was invited to tour PS/IS 128 in person and witnessed the safety measures in action.

Staff members check the temperatures of the children as they are dropped off each day.

As soon as children walk through the front doors, they are greeted by a row of staff armed with forehead thermometers to check for a fever as they hug their parents goodbye.

Those parents who were interviewed by CNN described the center as a “godsend” and “lifesaver.”

Isabela Borowski, whose 5-year-old daughter is starting kindergarten in September, said she felt comfortable with the REC after walking through the facility with an employee, and seeing all the masks and handwashing.

If a child doesn’t show up on site with their own face covering, they are now provided with a mask, and every student and staff member must wear one throughout the building.

Students are also reminded how to keep their distance by looking at the measurements of a giant sea turtle on the wall of the first floor — and they use air kisses, elbow bumps and arms outstretched like airplanes to walk through the hallways.

“We have a couple of teachers who do air hugs, so the other day I went into the classroom and there’s a little girl sitting back, just staring at me with this big smile and she’s going like this,” Ramage recalled, her arms crossed around her body. She said the girl was bubbling with enthusiasm for her new trick. “We’re trying to keep it fun.”

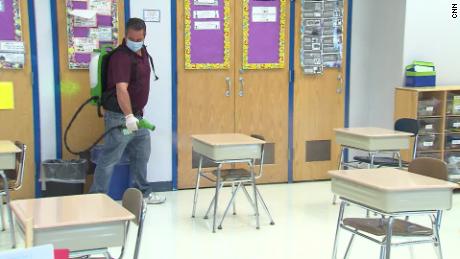

Classrooms used for looking after the children of essential workers are cleaned frequently.

Classrooms are limited to only nine children and sprayed down with an industrial-strength cleaning solution at least once a day.

If a child falls ill during the day — which Ramage says has happened only twice — there are “isolation rooms” and parents are called to come pick the child up. But so far, not a single case of Covid-19 has been reported.

The YMCA, which has also served tens of thousands of children throughout the country over the course of the pandemic, has used a similar model.

Leveraging its existing space, local YMCAs have been able to turn gyms into child care facilities, and found creative ways to keep children engaged in safety protocols, such as using a hand stamp that has to be scrubbed off to teach proper hygiene.

But safety comes with a steep cost, making all of these enhanced measures and protocols unrealistic for some school districts to put into practice on a large scale.

“Many of our YMCAs operate on a very small margin in traditional times anyway,” explained Heidi Brasher, a senior director for the YMCA of the USA. So now, with increased sanitation needs, the group is looking to donors, community members and local governments for help with the financial burden.

Josephine Ramage, site supervisor at the Queens center, is getting many calls about how she has kept staff and children safe.

And even cost issues aside, many practical challenges exist. Unlike regular schools, child care centers like the one at PS/IS 128 operate differently with no set arrival time for students in the morning, essentially offering “rolling admission” throughout the day once parents clear the approval process with the New York Department of Education, and new families crop up weekly.

“It’s not like a school where you know that you’re going to have this many kids in the classroom, these are the names of the kids,” Ramage said, explaining that every new family requires “onboarding” and potentially changing the schedule “because once we go past nine students, now we have to open a new classroom. I got to get new teachers in here. I got to teach them all the new protocols.”

And even the temperature check system would prove too taxing without staggered arrivals, said Ramage.

“Imagine the line that would be out the door, trying to keep them distanced and checking their temperatures,” she added. “So while the safety protocols are awesome, the cleaning products and just the procedures are a model, it’s not the same as school.”

CNN’s Meridith Edwards contributed to this report.

![]()