Fans hope Marvel comic book improves Native representation

Past portrayals of Native American or Indigenous comic book superheroes would often follow the same checklist — mystical powers, an ability to talk to animals and a costume of either a headdress or a loincloth.

“Poor research was done. They were just going off of TV and film,” said artist Jeffrey Veregge of the Port Gamble S’Klallam Tribe in Washington state. One of his biggest complaints is that mainstream “heroes from every place else had actual costumes” while Native characters weren’t represented well.

Growing up reading comic books on his tribe’s land outside Seattle, Veregge related more with non-Native heroes like Iron Man or Spider-Man. Now, he’s “living a dream,” overseeing a Marvel comic book about Native stories told by Native people.

Marvel Comics announced this month that it’s assembled Native artists and writers for “Marvel Voices: Indigenous Voices #1,” an anthology that will revisit some of its Native characters. It’s timed for release during Native American History Month in November.

Native comic book fans hope it’s a new start for authentic representation in mainstream superhero fare. Marvel says the project was planned long before the nation’s reckoning over racial injustice, which has prompted changes including the Washington NFL team dropping its decades-old Redskins mascot.

“It’s correcting a problem that started a long time ago,” Veregge said of the comic book project.

Veregge, who has drawn more than 100 covers for Marvel and other major comic book publishers, was a natural fit to lead the project. In February, he wrapped up an exhibit at the Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian in New York City. “Of Gods and Heroes” was his interpretation of Marvel protagonists like Black Panther and Thor, integrating shapes and lines inspired by tribal art styles.

“You want to make sure people recognize the characters themselves, but I also want them to see it’s a Native voice behind that,” Veregge said.

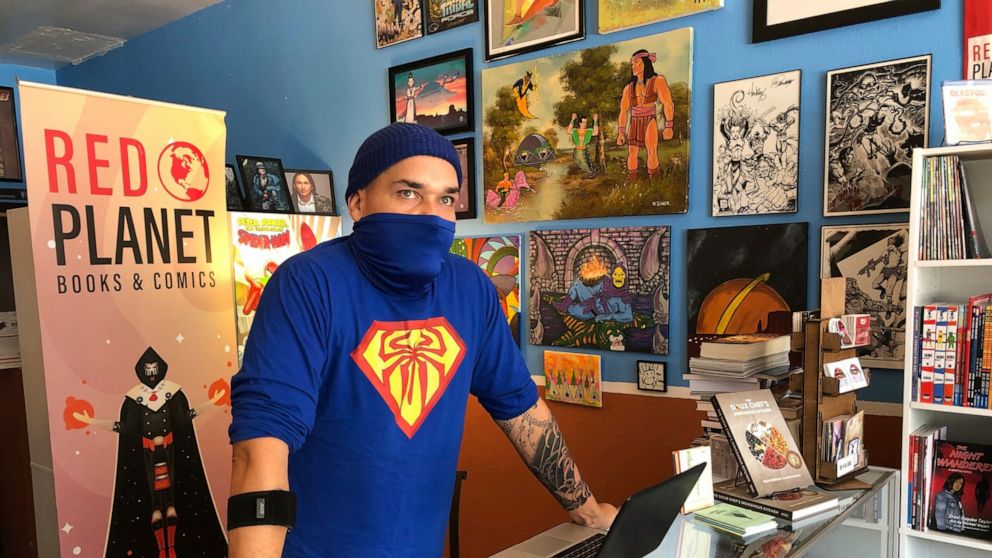

Lee Francis IV, owner of Red Planet Books & Comics in Albuquerque, New Mexico, and an independent publisher of Native comics, helped find up-and-coming Native artists to join the Marvel anthology. An organizer of an annual Indigenous Comic Con who’s descended from the Laguna Pueblo, Francis said comic books aren’t far off from some tribes’ storytelling traditions.

“I don’t want to speak for all Native folks, but I think there’s a visual acuity and storytelling sense that aligns perfectly with the comic book medium,” Francis said. “Not only words and writing, but this visual storytelling that harks back to our own stories and petroglyphs — rock art — ties it back to our ancestors.”

Racist stereotypes found their way into the medium because comic book artists often relied on what they saw in movie and TV Westerns, Francis said. And before Westerns, political cartoons dating to the 1700s demonized or ridiculed Native people.

For so long in comics, Native Americans have either been the villain or the stoic sidekick. It’s frustrating when a genuine “Indigenerd” sees “everybody else gets spandex and you get a headdress,” Francis said.

Dezbah Evans, meanwhile, always identified with Marvel’s “X-Men.” The series about young mutants struggling with powers while being persecuted by society seems to parallel how America treats Indigenous communities, said Evans, a 24-year-old comic book fan and cosplayer from Tulsa, Oklahoma, who’s Navajo, Chippewa and Yuchi.

She’s looking forward to the Marvel book because it will feature one of her favorite mutants — Danielle Moonstar, a Cheyenne heroine who conjures illusions based on people’s fears.

“It’s very validating that these are my peers, these are people I see at conventions and I’ve had relationships with,” Evans said of the writers and artists creating the book. “I’m really proud they’re able to get to this level.”

She hopes it’s the beginning of an expansion of the comic book world — not just the Marvel Universe. Mainstream pop culture still has far more Native male superheroes than female ones.

“Whenever I think of super Native women, they’re all mothers — my mom, my grandma. They’re the first heroes in all of our lives,” Evans said. “It would be really interesting to have a modern Indigenous mom living and being a superhero.”

Verland Coker, 27, a comic book fan of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation in Oklahoma, calls Marvel’s endeavor a step in the right direction but says comic books could go further.

It’s rare, for instance, to see Native superheroes talk in their own language. Incorporating some language would be an opportunity to educate non-Natives and promote tribes — many of which are struggling to preserve their language for younger generations, said Coker, who lives in Albuquerque.

“My worry is that we can occasionally lean into the monolith myth, and while any representation is great, we often only get a select few tribes,” Coker said via text. “I just would like to see more Native artists on mainstream products.”

That may not be far off based on the reception Veregge gets. When he meets children on the reservation where he grew up or at comic book conventions, their parents like to point out his work for Marvel. It’s an interaction he takes seriously.

“I get to tell kids: ‘I grew up on this reservation, too. You can do this, too,’” Veregge said. “I know who I’m representing. … I carry them wherever I go.”

———

Tang reported from Phoenix and is a member of The Associated Press Race and Ethnicity team. Follow her on Twitter at https://twitter.com/ttangAP.

![]()