When a coronavirus vaccine comes on the market, people will likely need two doses, not just one — and that could cause real problems

Some of the potential problems are logistical. Difficulties procuring test kits and protective gear throughout the pandemic point to supply chain issues that could also plague distributing double doses of vaccines for an entire country.

Other potential concerns are more human. Convincing people to show up to get a vaccine not once, but twice, could be a formidable undertaking.

“There’s no question that this is going to be the most complicated, largest vaccination program in human history, and that’s going to take a level of effort, a level of sophistication, that we’ve never tried before,” said Dr. Kelly Moore, a health policy professor at Vanderbilt University.

So far, Operation Warp Speed, the federal government’s effort to get a vaccine on the market, has given money to six pharmaceutical companies.

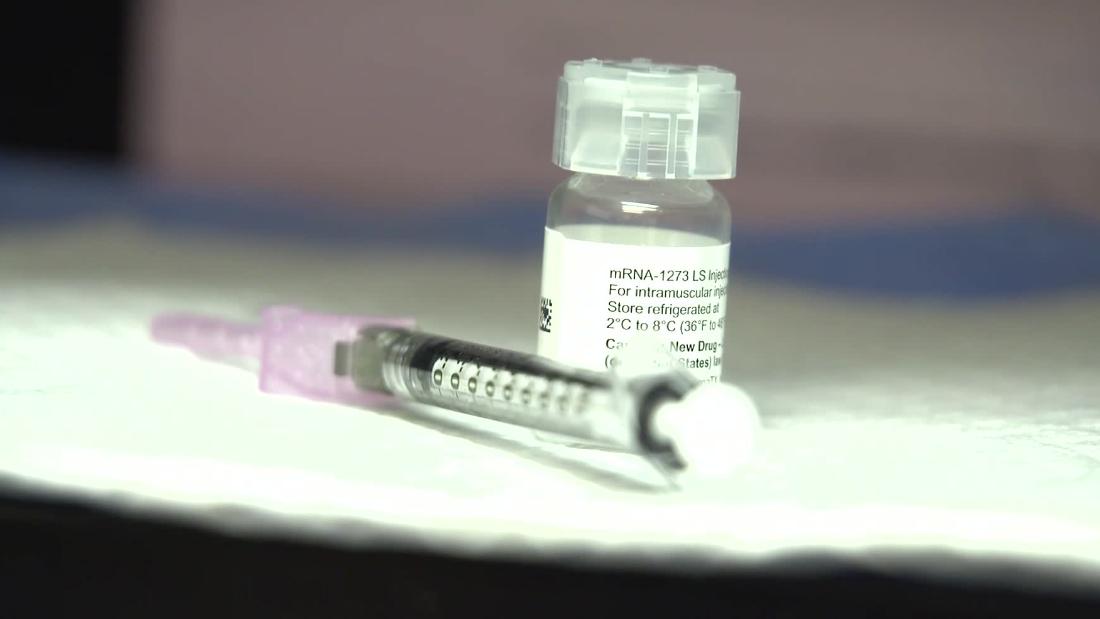

Two of those companies, Moderna and Pfizer, are now in Phase 3, large-scale clinical trials. The 30,000 volunteers in each of the trials are getting two doses, with Moderna spacing their shots out 28 days apart and Pfizer spacing theirs out by 21 days.

AstraZeneca is expected to start Phase 3 trials this month. Their Phase 1 and Phase 2 trials used two doses given 28 days apart.

Novavax also has yet to begin Phase 3 trials but used two doses in their earlier trials.

In Johnson & Johnson’s upcoming Phase 3 trials, some participants will take one dose and others will take two doses.

Sanofi hasn’t made announcements about whether their vaccine will be in one or two doses.

It’s not surprising that the coronavirus vaccine will likely need two doses. Many vaccines — including childhood vaccines for chickenpox and Hepatitis A and an adult vaccine for shingles — require two doses.

Some require even more — children get five doses of the DTaP vaccine, which protects them against diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis.

That means the upcoming coronavirus vaccine program will be difficult — but not impossible — to pull off.

“I have faith we can do it, but it is a big ask and we have to work with people to make it work,” Moore said.

Logistical issues

First, making 660 million doses for 330 million Americans is a tough feat.

“We’re looking at double shots. That’s twice the amount,” said Nada Sanders, a professor of supply chain management at Northeastern University. “Doubling is a huge supply chain issue.”

It’s not just producing the vaccines itself.

“You have to double everything in the supply chain,” Sanders said. “The syringes, can they double up? Can the vials double up? Can the stoppers double up? Can the needles double up? Everybody has to double up, and then they all have to get it in time at the various entities along the supply chain.”

Sanders says she’s worried, given the history of the Covid-19 pandemic in the US thus far has been rife with logistical problems, including delays in getting tests out on the market, and difficulties supplying health care workers with protective gear.

Starting even before the pandemic, there have been shortages of Shingrix, a vaccine for shingles.

“We’re talking about such exactness, and we couldn’t get PPE right, so I’m concerned,” Sanders said. “There are many weaknesses across this supply chain — many. If we don’t address this now, the probability of failure is very high.”

Human issues

It looks like it’s going to be tough to get a majority of Americans to show up just once for a vaccine, let alone twice.

According to CNN poll conducted this month, 40% of Americans say they won’t get the vaccine, even if it’s free and easy to get.

Even for people who do want the vaccine, it’s still a bigger ask to get them to show up twice.

People will have to remember to come in the second time. They might have to take time off work – twice. They may have to wait in long lines — twice. And possibly experience unpleasant side effects, like fever — twice.

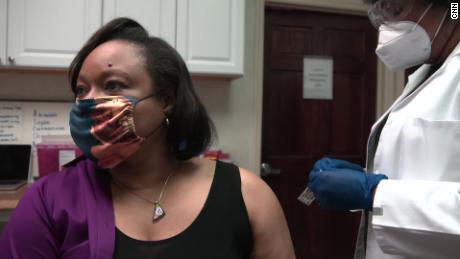

There are ways to address these hurdles, such as mobile clinics to bring vaccines to people rather than the other way around.

“These are the sorts of things that I think we need to think about, to make sure that we can incentivize people to come back to make it as easy as possible for them to adhere to a two shot regimen,” said Dr. Nelson Michael, director of the Center for Infectious Diseases Research at Walter Reed Army Institute of Research, who has been assigned to work with Operation Warp Speed.

Michael, who has worked on vaccine campaigns before, said even so, the challenges are real.

“I think if you give the public health community that remit, they will find a way,” he said. “But the task will be very difficult.”

![]()