The health care workers watching from afar as rich countries begin vaccine rollout

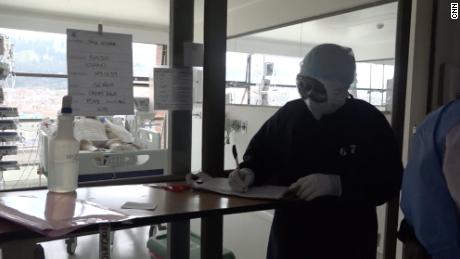

Velandia is proud of the hospital’s response to Covid-19 and recently showed CNN a new ICU facility that added 12 beds to the hospital’s arsenal. But he is also worried about his team — that same day, he said 5% of his staff was at home, sick with Covid. One was intubated in the emergency ward where they work.

Even for health workers who’ve avoided infection so far, fear and fatigue have crippled the unit after the near year-long pandemic.

“My team… They are tired, exhausted. They spend as many as 24 or 36 hours here, working all the time and we don’t have any more personnel,” Velandia told CNN.

Velandia looks with frustration at statistics on vaccine distribution in Europe and North America, where hundreds of thousands of frontline healthcare workers have already been vaccinated against the deadly virus. “I recently had a meeting, and my team was like ‘We can’t hold anymore’… we need the vaccine now!” he told CNN.

But like many countries in the developing world, Colombia is yet to receive a single dose of a vaccine.

Colombia’s conundrum

Colombian President Ivan Duque’s government was lauded last year by the World Health Organization (WHO) for its swift and well-coordinated pandemic response. After implementing social distancing measures early on, it increased the number of beds for intensive care, which almost doubled between March and August 2020, according to the health ministry.

But Colombia fell behind in the race to acquire vaccines. Now it finds itself essentially at the back of the queue, while nearby Brazil, Argentina, Mexico and Chile have already begun to administer the lifesaving inoculations.

Formally known as the Covid-19 Vaccines Global Access Facility, COVAX is an initiative co-led by the World Health Organization aimed at distributing vaccines to low-income countries who cannot easily purchase them directly from manufacturers. But it has not yet started dispatching vaccines anywhere in the world.

‘On the brink of a catastrophic moral failure’

WHO Director General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus has criticized wealthier countries for stockpiling excessive amounts, warning that unequal distribution between rich and poor countries could prolong the pandemic.

“I need to be blunt: the world is on the brink of a catastrophic moral failure — and the price of this failure will be paid with lives and livelihoods in the world’s poorest countries,” he said, while speaking at the WHO headquarters in Geneva on January 18.

But even among wealthy nations, trouble is already brewing as manufacturers struggle to meet delivery commitments. Last week, the EU introduced a measure requiring export authorization for vaccine makers with whom it had signed purchasing deals.

Some less wealthy countries have been able to ensure earlier vaccine access through clinical trial agreements. An analysis by Duke University’s Global Health Institute shows that some countries that participated in large scale vaccine clinical trials or with vaccine manufacturing capabilities were able to secure earlier doses and larger and advance market commitments from manufacturers.

“The investment to develop the vaccine has been enormous. Those who could not put in the money participated with volunteers for the trials,” Dr. Maribel Arrieta, an epidemiologist and spokesperson for Bogotá’s College of Doctors, told CNN. “And because of that, those who invested earlier are those who are receiving the vaccine now.”

How poorer countries will obtain vaccines

However governments acquire the vaccines, the WHO says it makes little sense for a limited number of nations to vaccinate their whole populations while the virus largely runs wild in the rest of the world. The organization is now calling for a radical re-thinking of how the vaccines are distributed.

“We must use them as effectively and as fairly as we can,” WHO Director General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus said on January 29. “That’s why I have challenged government and industry leaders to work together to ensure that in the first 100 days of 2021, vaccination of health workers and older people is underway in all countries.”

To do so could require wealthier nations to give up their current widespread vaccination goals, and share some of the vaccines they have already purchased with poorer nations, he said.

Beyond issues of fairness, it may also make more economic sense to vaccinate the most vulnerable worldwide instead of racing to achieve herd immunity among wealthy nations, Lawrence Gostin, the O’Neill Chair of Global Health Law at Georgetown University recently argued in Foreign Affairs.

Gostin and his co-authors cite research published in November by RAND Europe, a nonprofit global policy think tank, which estimates that the total GDP of high-income nations, including places like India, China, and Russia, would take a hit of around US$119 billion every year that low-income countries are unable to access vaccines, due to reduced spending in “high-contact intensive service sectors,” such as hospitality, recreation, retail and wholesale, transportation and health and social care.

“If these high-income countries paid for the supply of vaccines, there could be a benefit-to-cost ratio of 4.8 to 1. For every $1 spent, high-income countries would get back about $4.80,” RAND Europe says.

For Dr. Velandia at Soacha’s public hospital, each day without a vaccine means a new day of counting the human cost among his troops.

A couple of weeks after CNN’s visit to his ICU, Velandia told CNN that the intubated doctor had since recovered.

But another colleague had passed away from Covid-19, he said. “He was a therapist, his condition deteriorated really fast,” Velandia said. “A week ago, he was ok and working. We buried him yesterday.”

![]()