Court rules against Apaches in bid to halt proposed mine

A federal judge has rejected a request from a group of Apaches to keep the U.S. Forest Service from transferring a parcel of land to a copper mining company

FLAGSTAFF, Ariz. — A federal judge has rejected a request from a group of Apaches to keep the U.S. Forest Service from transferring a parcel of land to a copper mining company.

Apache Stronghold made the request as part of a lawsuit it filed against the Forest Service earlier this year. It’s the latest attempt to preserve the land in eastern Arizona that Apaches consider sacred because of the spiritual properties there at least temporarily while the court hears arguments on the merits of the case.

U.S. District Judge Steven Logan said Friday that because the group is not a federally recognized tribe with a government-to government relationship with the United States, it lacks standing in arguing that the land belongs to Apaches under an 1852 treaty with the U.S.

Even read liberally, Logan said “the court cannot infer an enforceable trust duty as to any individual Indians.”

For a favorable ruling, Apache Stronghold had to prove that the land transfer would cause imminent and irreparable harm and that it was likely to prevail on its claims, which include violations of religious freedom.

U.S. Department of Justice attorneys representing the Forest Service had argued Apache Stronghold didn’t do that, and Logan agreed.

“I am very disappointed but I’m not giving up,” Apache Stronghold leader Wendsler Nosie, Sr. said in a Friday night statement. “I’m excited to get back in there to also get an Appeal and once again to discuss where we disagree.”

The Tonto National Forest Service has said it does not comment on litigation.

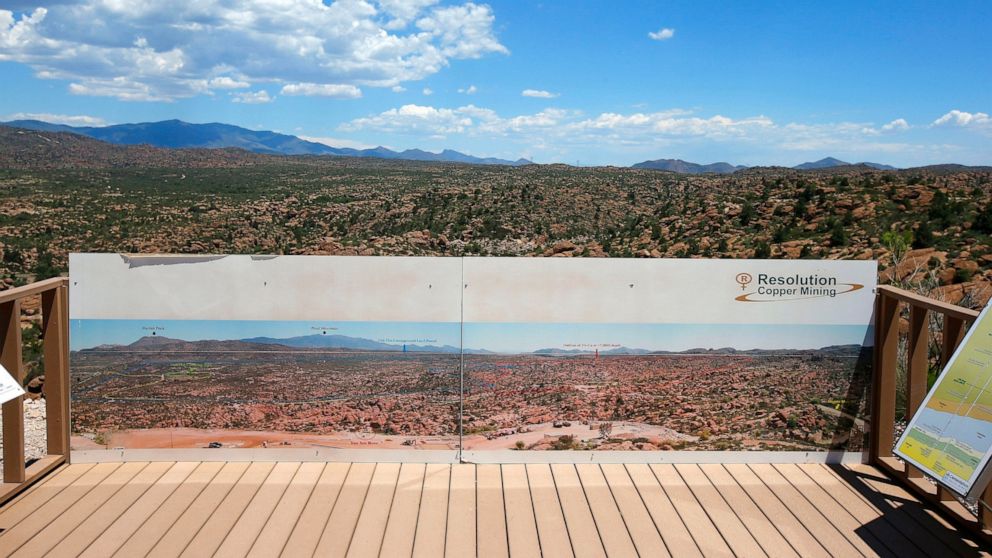

The land known as Oak Flat is set to be transferred to Resolution Copper by March 16, 60 days after the Forest Service published an environmental impact statement as mandated by Congress. The land transfer was included as a last-minute provision in must-pass defense bill in 2014 after it failed for years as stand-alone legislation.

Apaches call the mountainous area Chi’chil Bildagoteel. The land near Superior has ancient oak groves, traditional plants and living beings that tribal members say are essential to their religion and culture. Those things exist elsewhere, but Apache Stronghold said they have unique power within Oak Flat.

Logan acknowledged the mine would make Oak Flat inaccessible as a place of worship and “close off a portal to the Creator forever and will completely devastate the Western Apaches’ spiritual lifeblood.”

But he said the group didn’t meet the standard for proving violations of the Religious Freedom Restoration Act: being deprived of a government benefit or coerced into violating religious beliefs.

“It isn’t something the government gave to the Western Apaches, like unemployment benefits, and then took away because of their religion” Logan wrote in his ruling. “Similarly, building a mine on the land isn’t a civil or criminal ‘sanction’ under the RFRA.”

Attorneys for the Forest Service said the land legally belongs to the United States and that transferring its own property isn’t a substantial burden to the Apache group’s ability to practice its religion.

Resolution Copper, a joint venture of global mining giants BHP and Rio Tinto, has said it would not deny Apaches access to Oak Flat after it receives the land and for as long as it’s safe. But, eventually, the mine would swallow the site.

Resolution Copper has said the mine could have a $61 billion impact over the project’s expected 60 years and employ up to 1,500 people. It would be one of the largest copper mines in the U.S.

![]()