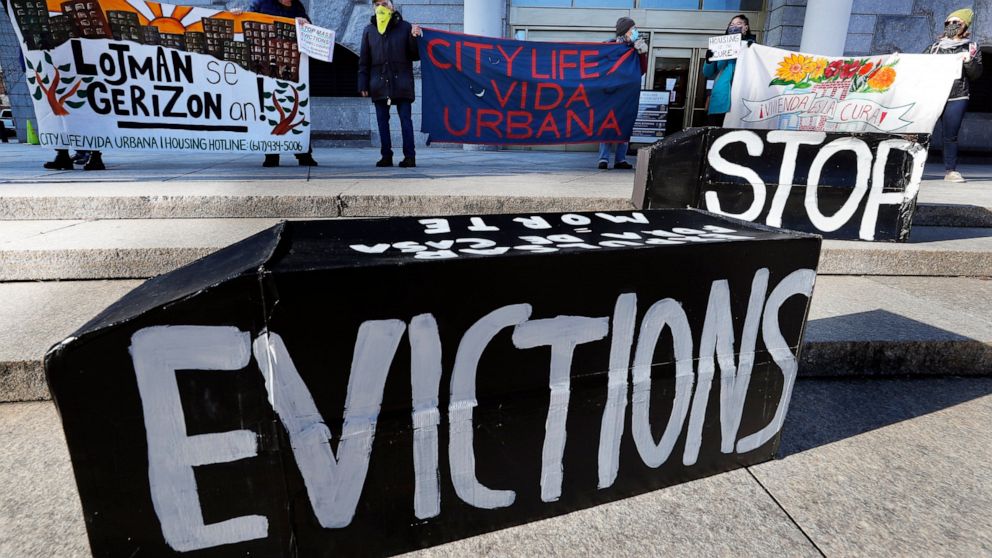

The eviction moratorium is expiring. What will Biden do?

WASHINGTON — President Joe Biden’s administration has less than a week to decide on extending the nationwide eviction moratorium, a measure that housing advocates say has helped keep most cash-strapped tenants across the country in their homes during the pandemic.

Housing advocates are confident the ban, due to expire March 31, will be extended for several months and possibly even strengthened. Still, they argue the existing moratorium hasn’t been a blanket protection and say thousands of families have been evicted for other reasons beyond nonpayment of rent.

“The key to restoring and strengthening our economy is defeating COVID-19. To do that, we must keep people safely housed as we work towards vaccinating more people. This is what the American Rescue Plan does,” Sen. Jack Reed, D-R.I., said in a statement. “But for now, an extension of the moratorium is clearly warranted until more people are vaccinated, more supportive housing programs come on line, and more help is deployed.”

The White House has indicated it is weighing an extension of the ban. The Department of Housing and Urban Development did not respond to a request for comment on the issue.

Eric Dunn, director of litigation for the National Housing Law Project, noted signs that a decision has already quietly been made. Last week, Dunn said, a HUD official conducted a call with housing advocates to field opinions on a new, streamlined form that tenants can use in order to gain protection from eviction.

“Why would they be doing that if they didn’t plan to continue this for a while longer?” Dunn asked. “The question is: What is the extension going to look like?”

Dunn and others would like to see the moratorium extended and improved. Last week, more than 2,000 advocacy organizations signed on to a letter to Biden and new HUD Secretary Marcia Fudge urging them to extend the ban via executive order and also “address the moratorium’s shortcomings by improving and enforcing the order.”

Implemented in September by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, President Donald Trump’s directive was extended until the end of January. Biden extended it until March 31.

The rationale for the moratorium was that having families lose their homes and move into shelters or share crowded conditions with relatives or friends during a pandemic would further spread the highly contagious coronavirus.

To be eligible for protection, renters must earn $198,000 or less for couples filing jointly, or $99,000 for single filers; demonstrate that they’ve sought government help to pay the rent; declare that they can’t pay because of COVID-19 hardships; and affirm they are likely to become homeless if evicted.

Biden’s $1.9 trillion COVID-19 relief package included more than $25 billion in emergency rental assistance, plus more to help tenants who were behind on their utilities, but no extension of the eviction moratorium.

And while that money works its way out to citizens, the need for relief remains dire.

John Pollock, coordinator of the National Coalition for a Civil Right to Counsel, said current surveys show that 18.4% of all tenants owe back rent. That number also revealed significant racial disparity; the percentage of Black tenants behind on their rent was 32.9%.

Pollack called the ban “the only thing holding back the flood” of evictions that would spiral through the still shaky American economy. “That kind of wave won’t just affect the renters themselves; it will devastate communities, much as the 2008 mortgage foreclosure crisis did,” he said.

But simply extending the moratorium is not enough, advocates said.

One of the biggest changes being advocated is for Biden to make the ban’s protection’s automatic and universal. Currently, tenants have to take active steps to invoke the ban’s protections — which leads to exploitation of the uniformed.

“It’s often the most vulnerable that don’t have the information they need to be protected,” said Diane Yentel, president of the National Low Income Housing Coalition, citing recent immigrants and the elderly as those least likely to know their full rights. “It’s really been left to organizations like ours to get the word out,” she said.

Another flaw: Landlords in some jurisdictions have been initiating eviction proceedings in court, a tactic the Trump administration opened the door to in a much derided amendment to the ban.

“It has allowed landlords to have these evictions just teed up and ready to go,” Dunn said.

Many families have chosen to leave their homes at the first threat of legal proceedings, fearing that the eviction — even one still in the courts — would be a stain on their record that would make finding a home challenging.

Not everyone supports keeping the moratorium in place. Landlords in several states have sued to scrap the order, arguing it was causing them financial hardship and infringing on their property rights.

There are at least six prominent lawsuits challenging the authority of the CDC ban; so far three judges have sided with the ban and three have ruled against, with all cases currently going through appeals. One judge in Memphis declared the CDC order unenforceable in the entire Western District of Tennessee.

“Individual eviction cases are still heard by state court judges far and wide — many of who never liked the CDC halt order to begin with and were just itching for ways to circumvent it or disregard it,” Dunn said.

———

Casey reported from Boston.

![]()