California plan to ban community oil drilling far from final

SACRAMENTO, Calif. — Environmental groups were cautiously optimistic about California Gov. Gavin Newsom’s proposal to ban new oil and gas wells within 3,200 feet of schools and homes, but the oil industry and labor allies warned the plan would raise California energy prices and potentially bring political consequences for the governor.

The ambitious proposal, announced Thursday, would create the nation’s largest buffer zone between wells and community sites, but it has a long way to go before it becomes official policy in the nation’s seventh-largest oil producing state. It would not shut down existing wells within the 3,200-foot (975-meter) zone but subject them to new pollution controls.

Newsom’s administration pointed to studies that show living near a drilling site can elevate the risks of birth defects, respiratory problems and other health issues. More than 2 million Californians are estimated to live within that distance of drilling, mostly in Los Angeles and Kern counties.

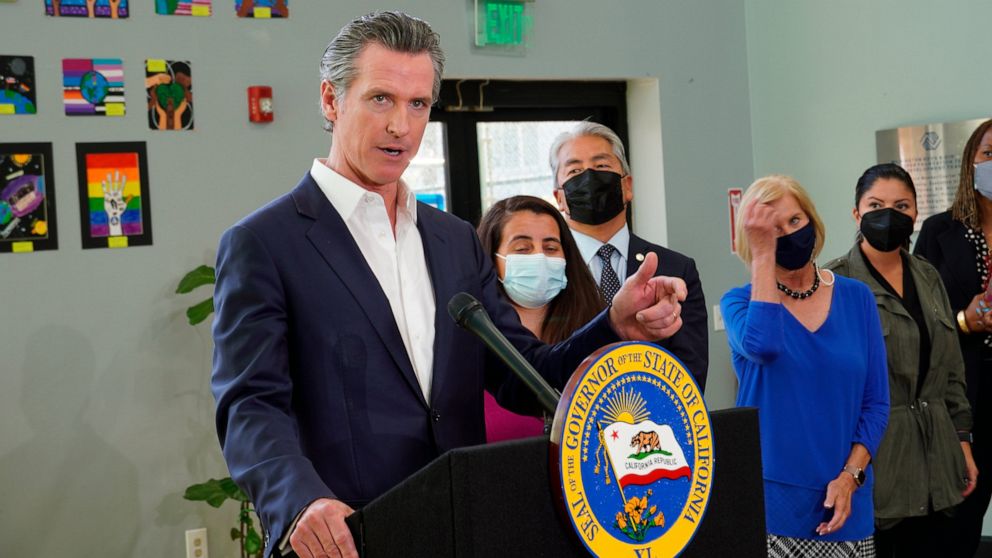

“This is about public health, public safety, clean air, clean water — this is about our kids and our grandkids and our future,” Newsom said in Wilmington, a Los Angeles neighborhood with the city’s highest concentration of wells. “A greener, cleaner, brighter, more resilient future is in our grasp, and this is a commitment to advance that cause.”

It’s the latest in a series of bold proposals the Democratic governor, who just survived an attempted recall, has made to wind down oil and gas production in California, which holds significant sway over national policy. He has directed state agencies to create plans to halt production by 2045 and end the sale of new gas-powered cars by 2035.

But some environmental groups, particularly those that represent low-income people and communities of color most affected by pollution, want him to act more swiftly. They were encouraged by the proposal but want to see Newsom take a more aggressive stand against existing neighborhood drilling.

In a statement, Juan Flores, a community organizer with the Center on Race, Poverty & the Environment, said the plan “misses the chance to prohibit new permits for existing wells, a key element for our communities.”

On the other side, the Western States Petroleum Association, an oil and gas lobbying group, and the State Building and Construction Trades Council, a union, warned the rule would make energy less reliable in California, forcing the state to buy more oil from other nations and leading to a spike in prices. In the past, efforts to create setbacks have failed in the capital, where the two groups are influential.

“I think the people of California are going to get (Newsom’s) attention when prices go through the roof,” said Robbie Hunter, president of the union. He said the rule was designed by “extreme environmentalists.”

The oil industry directly employs about 150,000 people in California, according to the Western States Petroleum Association.

The state will now open a 60-day public comment period, then the rule will go through an economic analysis. It won’t take effect until at least 2023.

Newsom painted California as taking a more aggressive stand than any other state on how close drilling can be to homes and schools, but the state is behind its fellow oil and gas producing states. Colorado, Pennsylvania and even Texas have rules about how close oil wells can be to certain properties. Colorado’s 2,000-foot (nearly 610-meter) setback on new drilling, adopted last year, is the nation’s strictest rule.

But California’s proposed plan goes further than the 2,500 foot (762 meter) buffer environmental groups sought. A 15-member panel of experts convened by the state said “studies consistently demonstrate evidence of harm at distances less than 1 kilometer,” which is slightly more than 3,200 feet. The panel acknowledged that no specific studies have been conducted to identify the safest distance between drilling and communities.

Existing oil and gas wells that fall within that distance will not be forced to close if the proposal is adopted. But they would be subject to a host of new burdensome and expensive pollution control rules, including leak detection and response plans, vapor prevention, water sampling and restrictions on light and sound pollution in the middle of the night.

The rules were proposed by the California Geologic Energy Management Division, known as CalGEM, which regulates the state’s oil industry and issues drilling permits. Newsom directed it to focus on health and safety when he took office in 2019, specifically telling the division to consider setbacks around oil drilling to protect community health.

CalGEM has long faced criticism that it’s too cozy with the industry it regulates. Wade Crowfoot, secretary of the state natural resources agency, acknowledged the regulator needs to better enforce oil companies’ compliance with state law.

There are about 18,000 active wells within the 3,200-foot zone, said Lisa Lien-Mager, spokeswoman for the California Natural Resources Agency. Community sites include homes and apartments, preschools and K-12 schools, day cares, businesses, and health care facilities such as hospitals and nursing homes.

Environmental advocates say they will be closely watching the process to make sure the final rules protect people living near drilling sites and, if the rule takes effect, that state regulators actually enforce it.

“This is an incredibly long-fought-for first step to getting us to stop drilling where people live, work and play, but we’ll see how the regulations end up,” said Martha Dina Argüello, executive director for Physicians for Social Responsibility, Los Angeles.

Jared Blumenfeld, California’s environmental protection secretary, said the new pollution control rules signal to existing drillers that “they’re going to have to invest a significant amount of time, money and attention in order to get into compliance.”

![]()