2021 in Books: `Everything feels magnified’

NEW YORK — Books and authors mattered in 2021, sometimes more than the industry wanted.

A 22-year-old poet became a literary star. The enthusiasms of young people on TikTok helped revive Colleen Hoover’s “It Ends With Us,” and other novels released years earlier. Conservatives pushed to restrict the books permitted in classrooms at a time when activists were working to expand them. And the government decided that the merger of two of the country’s biggest publishers might damage an invaluable cultural resource: authors.

“Everything feels very magnified,” says the prize-winning novelist Jacqueline Woodson, whose books have been challenged by officials in Texas and elsewhere.

“One day I hear that Texas is trying to ban (the Woodson novels) ‘Red at the Bone’ and ‘Brown Girl Dreaming,’ and the next moment we see Amanda Gorman speaking truth to power. Maybe it’s because of social media or the pandemic, but it all feels much more intense,” she says.

Sales were strong in 2020, the first year of the pandemic, and climbed higher in 2021. The number of books sold through the end of November increased by 10% over 2020, and by 20% over the pre-pandemic year of 2019, according to NPD BookScan, which tracks around 85% of the print market. The Association of American Publishers reported revenues of $7.8 billion for trade books through the first 10 months of 2021, a 14% jump over last year.

“You’re not hearing much these days about how people don’t read anymore,” says Allison Hill, CEO of the American Booksellers Association, the trade group for the country’s independent bookstores.

A year after the ABA worried that hundreds of stores could shut down because of the pandemic, Hill says membership is growing, with more than 150 new stores opening and around 30 going out of business.

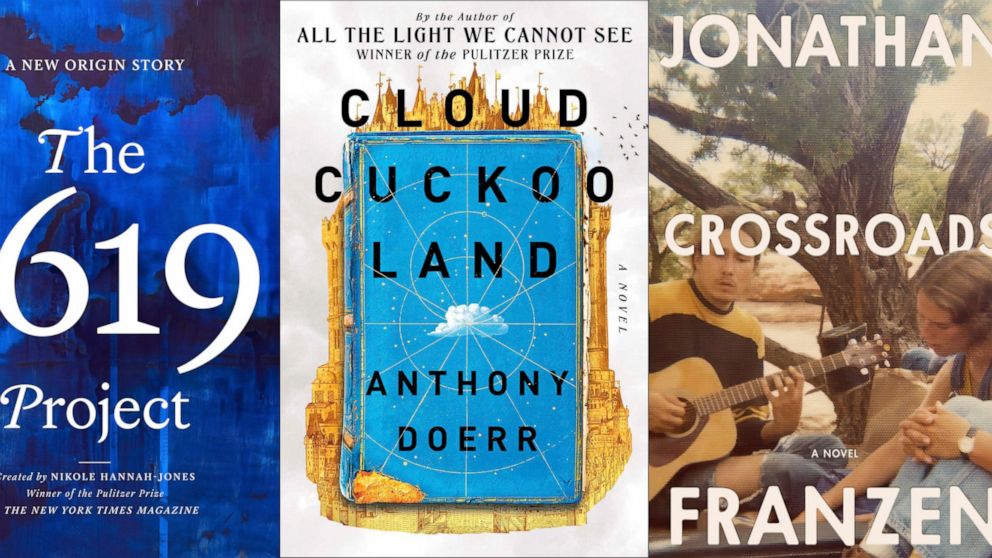

Fiction was especially strong in 2021 as sales tallied by BookScan jumped more than 20% from the previous year, driven by everything from TikTok and Reese Witherspoon’s book club to a surge in manga and a wave of literary bestsellers that included Jonathan Franzen’s “Crossroads” and Anthony Doerr’s “Cloud Cuckoo Land.”

The CEO of Penguin Random House U.S., Madeline McIntosh, called the popularity of fiction “the greatest sign we have of long-term growth for the industry.”

“It’s one thing when you’re grabbing books when you want to learn how to do something or to keep with current events, but it’s a different impulse when you’re grabbing a book because you want to fill your hours with reading. And that’s what we’re seeing with fiction,” she said.

With Donald Trump no longer in the White House, sales for political books dropped nearly 25%, according to BookScan. But the book world grew more politicized — starting with the question of who might, or should, release a memoir by the former president.

Multimillion-dollar deals for presidents have been a tradition. But New York publishers were uneasy with Trump before the Jan. 6 siege of the U.S. Capitol by his supporters and have since openly distanced themselves from him and such allies as Sen. Josh Hawley, whose “The Tyranny of Big Tech” was dropped by Simon & Schuster.

In response, a network of independent conservative publishers has emerged, whether such established entities as Regnery, which acquired Hawley’s book, or new companies like All Seasons Press or the Daily Wire’s DW Books. Trump’s first post-White House book project, the photo compilation “Our Journey Together,” will be released by Winning Team Publishing, founded by son Donald Trump Jr. and campaign aide Sergio Gor.

Throughout 2021, books made news. The year was barely three weeks old when millions watched Gorman become the country’s best-known poet and a cultural phenomenon. Her poised, forceful reading of her commissioned work “The Hill We Climb” was a highlight of President Joe Biden’s inauguration. It brought her recognition more in line with stars of fashion or movies, including a contract with IMG Models and a cover story for Vogue. A bound edition of “The Hill We Climb” sold hundreds of thousand of copies even though readers could find the text for free online.

Gorman’s appearance at the inaugural was made possible by first lady Jill Biden, who in 2017 had attended a reading Gorman gave at the Library of Congress as the country’s Youth Poet Laureate.

Countless authors, famous and little-known, found an unexpected supporter in Attorney General Merrick Garland. In November, the Department of Justice announced that it would sue to block Penguin Random House’s planned purchase of Simon & Schuster, the first time in years the government had tried to stop a major publishing consolidation. The DOJ’s objection was rooted as much in art as in commerce — concern that authors would not make enough money to write.

“Books have shaped American public life throughout our nation’s history, and authors are the lifeblood of book publishing in America,” Garland announced. “If the world’s largest book publisher is permitted to acquire one of its biggest rivals, it will have unprecedented control over this important industry. American authors and consumers will pay the price of this anti-competitive merger – lower advances for authors and ultimately fewer books and less variety for consumers.”

Woodson says she and other writers were stunned by the DOJ’s announcement and remembers thinking, “Wait, they’re speaking for us!”

The debates about literature were never more passionate than in the country’s classrooms and libraries.

Grassroots activists such as #disrupttexts.org pushed for teachers to diversify curricula with such novels as Woodson’s “Another Brooklyn,” Jesmyn Ward’s “Salvage the Bones” and Louise Erdrich’s “The Round House.” Independent bookstores worked to donate to schools free copies of the book-length edition of the Pulitzer-winning “1619 Project,” which places slavery at the center of American history. The book sold more than 100,000 copies in its first two weeks on sale, according to BookScan.

Meanwhile, an ad for Virginia’s Republican gubernatorial candidate Glenn Youngkin, who won the race, featured a white conservative activist alleging that her son had been traumatized by an assigned high school text, “Beloved,” Toni Morrison’s Pulitzer Prize-winning novel about a Black woman who had fled enslavement and murdered her daughter rather than allow her to be captured.

Dozens of bills around the country have been proposed or enacted that call for restrictions on books seen as immoral or unpatriotic. A state legislator in Texas, Republican Matt Krause, sent a 16-page spreadsheet to the Texas Education Agency listing more than 800 books he thought worthy of possible banning, including works by Woodson, Ta-Nehisi Coates and Margaret Atwood. Nine novels by the award-winning young adult author Julie Anne Peters, whose narratives often feature LGBT characters, were cited.

“I think one reason this happens is because books have staying power,” Peters said. “You always remember the great books you’ve read. They are so influential, especially the ones in school. Everything else is so fleeting, and changes. But once a book is there and it’s available and it represents our history and our culture, it becomes a historical reference you go back to.”

![]()