“What we’re seeing right now is unprecedented,” says Joanna Lydgate, co-founder and CEO of States United Action, a bipartisan group tracking threats to election integrity across the country. “To see candidates running on a platform of lies and conspiracy theories about our elections as a campaign position, to see a former President getting involved in endorsing in down-ballot races at the primary level, and certainly to see this kind of systemic attacks on our elections, this spreading of disinformation about our elections — we’ve never seen anything like this before as a country.”

And even as these candidates are advancing, Republican legislators are moving a flurry of bills to

change the rules for both voter access and election administration. Down one track, as has been widely reported, 19 Republican-controlled states

approved bills in 2021 making it more difficult to vote. Less widely discussed has been a second track: an exhaustive

study released last week by three election reform groups found that 13 states have already approved laws allowing for more partisan control of election administration, imposing greater penalties on election administrators for alleged violations, or requiring highly partisan audits of the 2020 results, with another 229 bills still pending in 33 states.

“Taken separately, each of these bills would chip away at the system of free and fair elections that Americans have sustained, and worked to improve, for generations,” the groups concluded. “Taken together, they could lead to an election in which the voters’ choices are disregarded and the election sabotaged.”

This two-front offensive revolving around efforts to both change the election laws and who administers those laws could reconfigure the fundamental landscape for the 2024 election much more than most Americans, or even many political leaders, seem aware. It could also thrust the nation into incendiary turmoil about the legitimacy of the next presidential result, no matter who wins.

“It’s all connected,” says Lydgate. “The playbook is to try to change the rules and change the referees, so you can change the results.”

Republicans echoing Trump’s claims and disputing the 2020 outcome include gubernatorial candidates in 24 states, secretary of state aspirants in 18 and attorneys general hopefuls in 14, according to

tracking by States United. That means election deniers are seeking nominations in about two-thirds of the states choosing governors and secretaries of state this year, and in about half of those selecting attorneys general.

“In the leadup to the 2020 election, those who warned of a potential crisis were dismissed as alarmists by far too many Americans who should have seen the writing on the wall,” Jessica Marsden, counsel at Protect Democracy, another bipartisan group tracking threats to future elections, wrote in an email. “Almost two years later, after an attempted coup and a violent insurrection on our Capitol, election conspiracy theorists — including those who actually participated in January 6 — are being nominated by the GOP to hold the most consequential offices for overseeing the 2024 election.”

The Republican Secretaries of State committee did not respond to a request for comment on the charge that some of its candidates could threaten the integrity of future elections.

Not all of these candidates, of course, will win GOP nominations for these sensitive posts. But the list is growing of election deniers who have already done so. The most prominent example came last week when Pennsylvania state

Sen. Doug Mastriano, who led Trump’s efforts to overturn the state’s results from 2020 and marched toward the Capitol on January 6 (though he says he didn’t enter the building),

won the GOP nomination for governor in the Keystone state.

In Michigan, the GOP state party convention recently nominated election deniers for both secretary of state and attorney general; Kristina Karamo, the GOP’s secretary of state nominee,

has flatly declared that Trump won Michigan (a state he lost by over 150,000 votes) and that leftist agitators actually carried out the attack on the Capitol. Karamo has also asserted that Jocelyn Benson, Michigan’s Democratic Secretary of State,

should be jailed.

The Minnesota Republican Party has endorsed as its secretary of state candidate another election denier, Kim Crockett, who played a video at the state party convention showing election officials (including the state’s Jewish Secretary of State Steve Simon) under the control of Jewish financier George Soros; the state GOP chair last week publicly apologized for the video (but defended Crockett). In Idaho, former US Rep. Raul Labrador last week ousted incumbent Attorney General Lawrence Wasden in a GOP primary that centered on Wasden’s refusal to join the

2020 lawsuit from Texas that sought to tip the presidency to Trump by invalidating the votes in four key states Biden won.

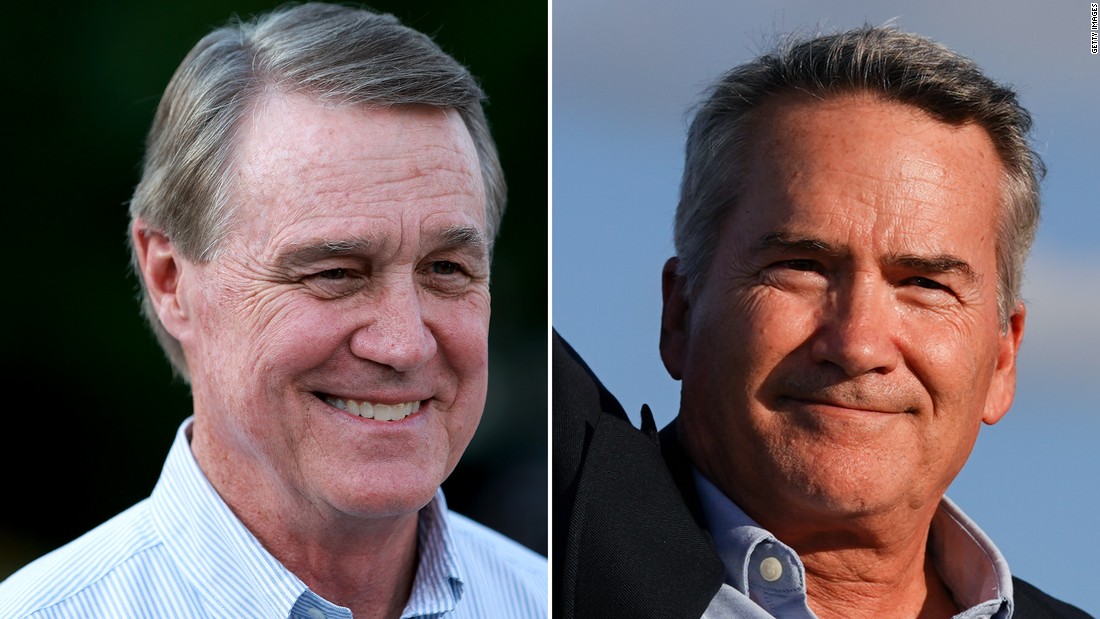

Georgia isn’t likely to expand this list as much as Trump hoped. Local leaders told me Trump angered Georgia Republican activists — even many who agree with his claims about 2020 — by targeting so many of the state’s GOP officials for primary challenges. In the marquee race, former Sen. David Perdue, Trump’s instrument for vengeance against Kemp, has run a listless campaign and is expected to be trounced. Attorney General Chuck Carr, another target of the former President’s ire, also appears likely to reach 50% of the vote and avoid a runoff against a Trump-backed challenger who has struggled to raise money.

But State Sen. Burt Jones, a Trump endorsee who has endorsed his conspiracy theories, is the front-runner in the race for lieutenant governor, after the Republican incumbent Geoff Duncan, who criticized the former President’s efforts to overturn the 2020 result, chose not to seek reelection.

And Rep. Jody Hice, the Trump-backed candidate for secretary of state, could force a runoff with Raffensperger, even though the incumbent has tried to buttress his conservative credentials by calling for amendments to the Georgia and US constitutions to prevent voting from non-citizens, which is already illegal. Hice has said Trump would have won Georgia in 2020 if the election was “fair” and

recently told reporters he saw nothing wrong with Trump’s call to Raffensperger, in which Trump pressured the secretary to “find” enough votes for him to win the state. (That call is at the center of an ongoing

Fulton County grand jury investigation of Trump.) A runoff would probably favor Hice because more moderate GOP voters might be less likely to turn out again to defend Raffensperger once the higher-visibility governor’s contest has been decided, says Charles Bullock, a political science professor at the University of Georgia.

However Georgia plays out, the conveyor belt of Trump-style election deniers is likely to continue advancing through GOP primaries. Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton, who led that lawsuit against the 2020 result, is favored to win his runoff primary Tuesday against Texas Land Commissioner George P. Bush. Candidates echoing Trump’s fraud claims are in strong positions to win GOP secretary of state nominations in June primaries in Nevada and Colorado (where the GOP convention gave the most support for the position to Tina Peters, the Mesa County elections clerk

currently under indictment for tampering with election equipment).

Election deniers are strongly positioned as well in the gubernatorial and secretary of state primaries in Arizona, where two leading contenders for the latter position are state legislators Mark Finchem and Shawnna Bolick,

who both signed a letter asking Congress to throw out the Arizona results and award the state’s Electoral College votes to Trump. (None of the major candidates for the GOP attorney general nomination in Arizona would agree Biden legitimately won the state when recently surveyed by the Arizona Republic.)

In Wisconsin, one of the GOP’s leading gubernatorial contenders, Lt. Gov Rebecca Kleefisch recently declared the 2020 election in the state was “rigged” despite multiple studies finding no evidence of fraud.

“These folks are running on platforms of preordained winners for 2024,” charges Kim Rogers, executive director of the Democratic Association of Secretaries of State. “It is not about counting ballots; it is about changing the results for their preferred candidate.”

The steady advance of GOP candidates parroting Trump’s claims reflects both the widespread acceptance of his fraud allegations among Republican voters — 70% of GOP partisans said Biden did not win the election legitimately in

a CNN poll earlier this year — and the refusal of any other key institutions in the Republican coalition, from elected officials to business leaders, to systematically push back against those claims. In Georgia, Trump has faced a generalized backlash over his heavy-handed intervention, but no specific effort emerged from business or elected Republicans to defend Raffensperger. In Colorado former state GOP chair Dick Wadhams sees the same thing. Asked if there was any effort in the party to contest the fraud claims, he replied: “To answer it very simply: no there isn’t.”

Ian Bassin, Protect Democracy’s executive director, says that pattern is apparent around the country, especially after Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis and the GOP-controlled

state legislature retaliated against Disney for its criticism of what opponents have called their “don’t say gay” legislation.

“Scholars of the rise and fall of democracies have identified the business sector as often one of the most important bulwarks against authoritarianism,” Bassin says. “But … the attitude inside too many C-suites today after seeing what happened to Disney is to keep their heads down and retreat from playing any role in the current battle for democracy.” Republican elected officials have been even more reluctant to challenge these claims: “This is where the failure has been the most extreme.”

In several of these Republican primary contests, the biggest threat to the election deniers may be multiple candidates splitting that vote. That’s what happened in the recent Idaho secretary of state primary when a more mainstream candidate, Ada County Clerk Phil McGrane, won with only 43% against two election-denying opponents. The same dynamic could play out in the Colorado and Arizona secretary of state races. And just as Raffensperger supporters are hoping that crossover Democratic voters might bolster him in Georgia, Wadhams says more independents than usual might participate in the Colorado GOP primary to block Peters and gubernatorial aspirant Greg Lopez, who has said that if elected he would pardon her. (Lopez has also endorsed an “electoral college” type system for statewide elections that would end one-person, one-vote and magnify the influence of rural areas.)

Both at the national and state level, Democrats have not found a way to make these potential threats to democracy tangible or relevant to voters, analysts in both parties agree. The prospect that the

Supreme Court may overturn the

right to abortion could give them a second chance by bundling threats to voting and election integrity into a larger argument that Republicans are trying to roll back rights across a broad front.

Pennsylvania Attorney General Josh Shapiro, who won the Democratic gubernatorial nomination last week, may have made the most progress in the party toward forging that argument. “It’s not freedom when they get to dictate to the women of Pennsylvania how and when and under what terms they’re going to start a family. It’s not freedom when they tell our children what books they can read. And it sure as hell isn’t freedom when they go out and say, sure, you can vote, but we get to pick the winner,” Shapiro insisted in a recent television appearance.

Such arguments may prove effective in some places. Yet in a midterm political environment

so favorable for Republicans, it’s highly likely some of the candidates trumpeting Trump’s big lie will win positions providing them control over election administration and tabulation — and that could present unprecedented challenges sooner than later.

“There could be chaos in 2024,” says Wadhams, the former Colorado GOP chair. Chillingly, that chaos could be the most intense precisely in the states most likely to decide the next race for control of the White House.

![]()