‘The horse and buggy era’: Attacks on voting machines set off fresh worries about election subversion

Commissioners in Nye County, Nevada, meanwhile, want local election officials to begin hand-counting paper ballots in this year’s elections.

Reverting to hand-counting would “take election administration back to the horse and buggy era” and is “wildly impractical” for large jurisdictions with millions of voters, said Victoria Bassetti, a senior adviser to the States United Democracy Center, a nonpartisan group working on fair and secure elections.

Bassetti called the moves “dangerous for democracy and driven by senseless conspiracy theories about the 2020 election.”

Rachel Homer, counsel at the voting rights group Protect Democracy, said the attempts to return to laborious hand-counting increase the risk of election sabotage because they could “empower partisan actors to say, ‘We can’t know who the winner is, so I declare this person the winner.'”

Trump has also cheered on efforts to yank the machines, praising the lawsuit recently filed in Arizona by Republicans Mark Finchem and Kari Lake — candidates he has endorsed for secretary of state and governor, respectively.

“Every state should follow the lead of the patriots in Arizona,” Trump told rallygoers near Columbus, Ohio, in April.

The Arizona case seeks to bar the use of electronic voting machines in the state’s midterm elections unless the system is opened to “the public and subjected to scientific analysis by objective experts to determine whether it is secure from manipulation or intrusion.”

‘Soul-crushing’ chore

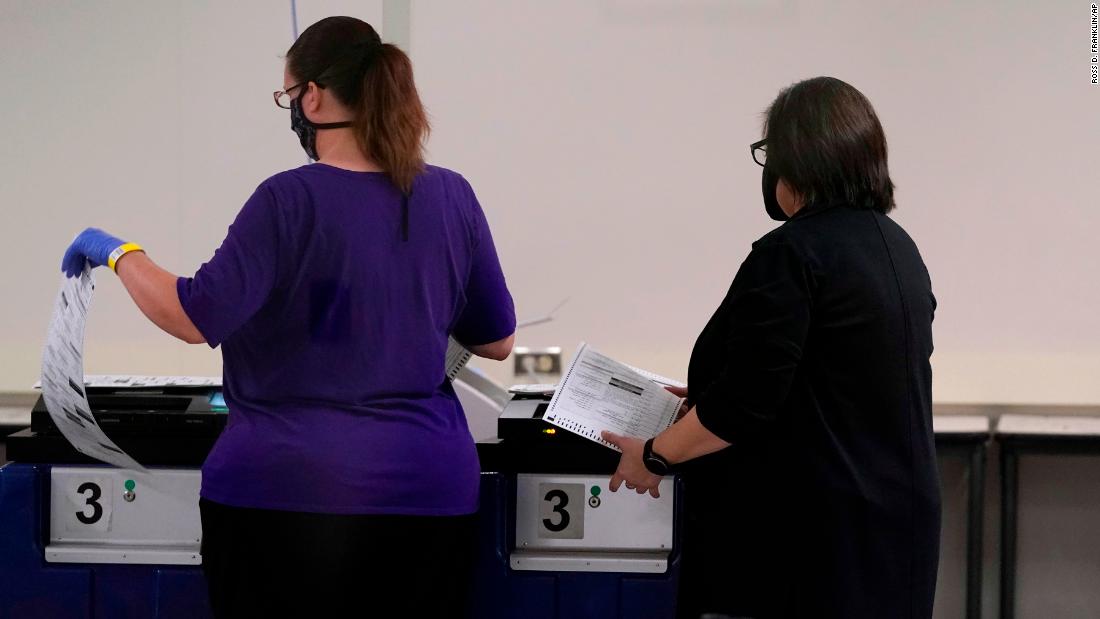

Most election offices use machines to tabulate votes, and hand-counting ballots is largely confined to smaller jurisdictions, said Mark Lindeman, director of Verified Voting, a nonprofit organization that specializes in election technology issues.

The group estimates that a just tiny slice of the population — roughly 444,600 voters — live in communities where ballots are still counted by individuals. More than 209 million Americans were considered active registered voters during the 2020 general election, according to the US Election Assistance Commission

Hand-counting is “soul-crushing” manual work that’s prone to human error, Lindeman said. Instead, he argued, the best practice is to “let the technology do what it’s good at and intelligently check to make sure it’s doing it right.” That includes performing post-election audits in which a sample of ballots is hand-counted and those totals checked against the machine tallies.

Local lobbying

But the county’s elected clerk, Sandra “Sam” Merlino, warned commissioners that replacing machines with paper ballots and requiring hand-counting could prove costly and likely contravenes state and federal laws that require electronic voting options for disabled residents. She said the proposal would need more research.

Despite those reservations, commissioners voted 5-0 to urge Merlino to use paper ballots for voting and to ditch tabulating machines in this year’s primary and general elections.

Marchant did not respond to interview requests from CNN, nor did Commissioner Debra Strickland, who brought the issue to the commission after hearing a presentation from a tea party group. “The people have been concerned for some time about whether or not our votes are being processed,” Strickland said at the meeting where commissioners debated the change.

Frank Carbone, the chair of the Nye County board of commissioners, declined to comment.

In an interview with CNN, Merlino called hand-counting a “monumental task” in a county with some 30,000 voters. She plans to continue to use machines in the fast-approaching June 14 primary.

But the controversy has hastened her departure from a job she has held for more than two decades.

She said she’s moved up her year-end retirement plans and will leave her post in August instead — rather than face the prospect of a fresh confrontation over machines and hand-counting in November’s general election.

“I’m retiring early because I don’t want that to be my last election,” said Merlino, who has served as clerk since January 2000. “I kind of wanted to retire on a good note, but now I just want to slink out the door. No one trusts anyone.”

The commissioners have the authority to appoint Merlino’s replacement, who will oversee the general election in November.

Boots Campbell, the county’s elected clerk and recorder, estimated that it would take “two weeks, maybe going into three” to know the results if she were forced to count the ballots by hand — even in a county with just 4,800 active voters because of staffing constraints. “And then can you trust a hand count?” she said. “I don’t think so.”

The move also drew a stern letter from the Colorado secretary of state’s office, warning that eliminating all machines in upcoming elections would violate state and federal law.

Earlier this month, one of the commissioners who favored hand-counting lost his seat in a recall election. Another has resigned.

So, Campbell plans to urge the new board to restore the funding at a meeting next month. She must pay Dominion by October 1 to guarantee the machines’ use for November’s general election.

![]()