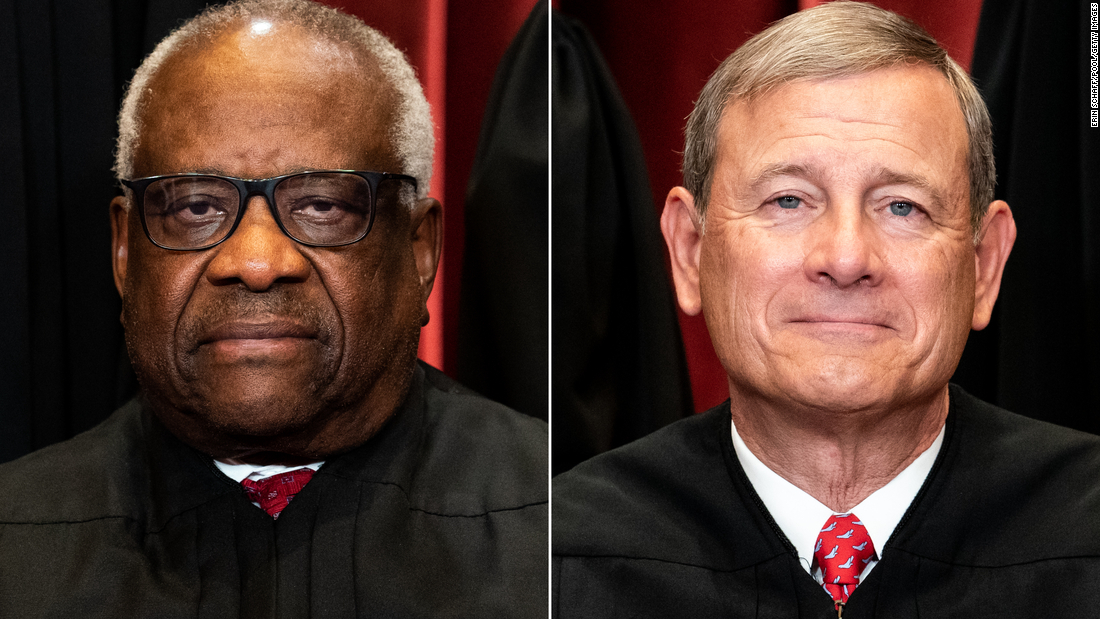

In a recent appearance, Clarence Thomas’s message to the chief justice came down to this: The court was better before you arrived

Roberts announced that 30 years ago on that exact date, a ceremonial investiture for Thomas had been held. Thomas, sitting to Roberts’ right, beamed and slung his arm over the chief’s shoulder.

That collegiality in the courtroom, filled with only a few dozen spectators because of Covid-19 protocols, has vanished. The two justices are now engaged in an epic struggle over a new abortion case that could mean the end of Roe v. Wade nationwide and unsettle the public image of the court.

Thomas last week recalled the court atmosphere before 2005, when Roberts joined, and said, “We actually trusted each other. We may have been a dysfunctional family, but we were a family, and we loved it.”

Thomas’ blunt remarks suggest new antagonism toward Roberts and added to the uncertainty regarding the ultimate ruling in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, expected by the end of June.

Roberts, with his institutionalist approach, is positioned as the one justice who might generate a compromise opinion that stops short of completely overturning Roe v. Wade, at least this year. That would thwart an outcome that Thomas has worked toward for decades.

CNN previously reported that Roberts was trying to forestall reversal of Roe, even though he favors upholding the Mississippi ban on abortions after 15 weeks of pregnancy.

Thomas’ remarks pulled back the curtain on the tensions inside. Perhaps they revealed long simmering sentiment for a chief who has wrenched relations over the years. Or perhaps they reflected the internal recriminations over who might be responsible for disclosing the draft opinion. Or perhaps they indicate that the apparent five-justice majority to overturn Roe is not so secure.

It is not unusual to hear Thomas deride the court’s traditional adherence to precedent, what’s known by the Latin phrase of stare decisis. “We use stare decisis as a mantra when we don’t want to think,” he insisted in an Atlanta speech in early May.

But Thomas’ sudden aim at Roberts’ leadership is new. In the Dallas appearance, his message to the chief justice came down to: The court was better before you arrived.

As Thomas responded to a question about relations between justices, such as the celebrated friendship of the late Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Antonin Scalia, Thomas said, “This is not the court of that era.”

“I sat with Ruth Ginsburg for almost 30 years. And she was actually an easy colleague for me. You knew where she was (on legal questions), and she was a nice person to deal with. Sandra Day O’Connor, you could say the same thing.”

Thomas referred to the bench from 1994 to 2005, when the same nine were together with no change and said: “The court that was together for 11 years was a fabulous court. It was one you looked forward to being a part of.” (Thomas did not respond to a CNN request for an interview.)

The controversy over Roe v. Wade and the disclosed draft seemed to provoke most of his comments. Thomas has separately been at the center of another storm in recent weeks, tied to his wife, Virginia “Ginni” Thomas.

Thomas failed to recuse himself from cases involving the 2020 election and the January 6 riot at the US Capitol, at a time when, it has emerged, Ginni Thomas was privately urging Trump aides to press the legal case to reverse the results of the election that showed Joe Biden winning the presidency.

Two men, two styles

Thomas and Roberts have different negotiating patterns.

Thomas is known for putting his cards on the table and abhorring gamesmanship. The first attribute he ascribed to Ginsburg was revealing: “You knew where she was.”

Roberts, in contrast to Thomas, has a reputation inside the court for being guarded, even secretive.

Some conservatives still fault him for a late switch in votes to save the Obama-sponsored Affordable Care Act in 2012. In that instance and others when Roberts joined with liberals for a compromise, the shift stopped the court from reeling too far right and reflected his institutionalist interests.

Thomas has been most vocal over the years in condemning Roe, just as he opts to publicly dissent when the justices decline major issues.

This session, as the justices are poised to obliterate abortion rights, Thomas is also positioned to break ground on the Second Amendment in a New York case that raises issues related to the prior New Jersey dispute.

Roberts has a steep climb to craft a compromise that with keep Roe partially intact. The right-wing bloc allowed Texas’ virtual ban on abortions to take effect last year, and during oral arguments in the Mississippi case, it appeared to be holding together to eviscerate Roe. The two conservatives most likely receptive to Roberts’ appeal to slow down Roe’s reversal would be the newest: Brett Kavanaugh and Amy Coney Barrett.

Roberts has a case to make: When the justices first agreed to hear the Mississippi dispute last May, they said they were confining the dispute to the question of “whether all pre-viability prohibitions on elective abortions are unconstitutional.”

The draft opinion published by Politico, written by Justice Samuel Alito, rejects the court’s original 1973 reasoning that gave women a privacy right to end a pregnancy and contends the time has come to reverse Roe.

The persuasive force of Roberts, a former star appellate advocate who continues to pull together notable compromise decisions, cannot be discounted.

And the pending Mississippi case would have a far broader impact on constitutional privacy rights than the dispute over the Texas ban on abortions at roughly six weeks. Roberts, who dissented in that case, failed to persuade Kavanaugh, Barrett or any of the right-wing fivesome to shift.

If the draft as published by Politico were to become the final ruling, a half-century of women’s reproductive freedom would evaporate, and other personal privacy rights would be under threat.

Before this court session, the justices’ last review of abortion rights law came in 2020, when Ginsburg was still on the bench and Roberts cast the decisive vote to strike down a restrictive Louisiana abortion law. Roberts, who has opposed abortion rights in the past, based his vote on adherence to precedent.

And the justice who has increasingly found greater support for his views declared, “Our abortion precedents are grievously wrong and should be overruled.”

![]()