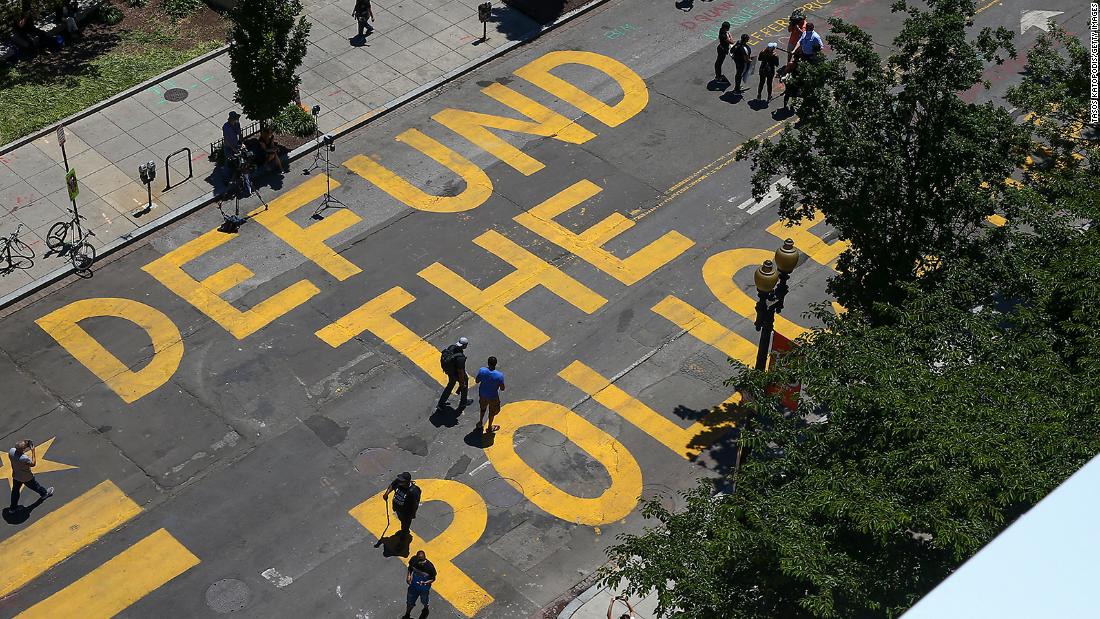

From the murder of George Floyd to the killings of Adam Toledo; Daunte Wright; Mario Gonzalez, Ma’Khia Bryant and Andrew Brown, Jr., we are having many of the same conversations about policing over and over. Many of us (like me) are getting frustrated that the conversations don’t evolve. Many of us are getting stuck in the same rhetorical cul-de-sacs. And some of you out there won’t even Google the thing that frightens you most about this conversation: Wait for it … “Defund The Police.”

Luckily, I see my role on “United Shades of America” as “CNN’s Head Googler,” so this episode gives both a deep dive on the Defund movement as well as how Defund is related to and different from the Abolition movement. We also do a deep dive on America’s racist history of policing. And we have no other choice than to talk about some of the truly horrific cases of police violence in our country. Yes, it is a lot to cover. Thankfully, CNN let this be an extended episode.

Grant was on his knees with his hands on his head, clearly complying, when Johannes Mehserle, the now ex-BART officer, shot him.

Mehserle later claimed that he thought he was reaching for his taser. If you can remember all the way back to two weeks ago,

that is the same reason given for former Brooklyn Park officer Kim Potter shooting and killing Daunte Wright.

Oscar Grant’s killing was 12 years ago. Once again, the headlines don’t change.

Aidge Patterson of the LA Coalition for Justice for Oscar Grant leads a protest rally in 2010. (MARK RALSTON/AFP via Getty Images)

And that is why so many people are way past talking about an increase in superficial reforms, such as police wearing body cameras, implicit bias training, or hiring more Black officers. Instead, they are calling for the defunding of the police.

Unlike elsewhere in the country, this conversation isn’t new in Oakland. I first heard about this movement when I moved back to the Bay Area in 2014 and I met Cat Brooks of the

Anti Police-Terror Project. Cat is an activist, artist, radio host, and maybe the future mayor of Oakland. Cat and APTP identified that one of the central problems of policing wasn’t training, or good apples vs. bad apples, or a lack of midnight basketball; it was money. As Cat says, “The Oakland Police Department gets almost half of our general fund. And when you look at Oakland in particular, all of these years we remain one of the top deadliest cities for violent crime in the country year after year after year. So, Oakland, what are we paying for?”

And if we are going to talk about Defund as a concept, let’s be clear on one thing: Americans are some of the defundiest defunders in the history of defunding stuff. We just don’t think of it as “defunding”; we have been trained to think of it as “budget cuts.” I am arguing that they are the same thing. Every time your local government cuts library hours, or cancels a bus line, or closes a public school against the wishes of the neighborhood

while prioritizing policing, that is taking funds away from the people who rely on what those things do — a.k.a., defunding. And when that happens, it generally happens in the Black and Latinx neighborhoods

that need the funds the most.

But law enforcement has convinced us that if crime is bad they need more money. But then they have also convinced us that

if crime is not that bad that they need more money to

keep it not that bad. In major cities across America, police departments generally soak up between 20% and 45% of municipal general funds, according to a

Statista review of data from the Center for Popular Democracy, the Law for Black Lives and the Black Youth Project 100.

In Baltimore, Maryland, for example, that means for every dollar that goes to police, public schools only receive 55 cents, a 2017

Center for Popular Democracy report found. The office that funds job programs gets five cents. Programs for substance abuse, mental health, and youth violence prevention each get one measly cent.

All that money going to police means that the police are tasked to do way too many things that they should never be doing. Like dealing with homelessness, substance abuse, mental health or patrolling the halls of schools.

Replace a historically racist institution

And there are also all the times police are asked to deal with something that is nothing, and people die. In the episode, we talk about the story of

Elijah McClain, the 23-year-old Black man in Colorado who was walking down the street, literally minding his own business, when someone thought he looked suspicious and called 911. (Again, he was literally minding his own business.)

Police showed up. Detained him. He tried to explain to them that he wasn’t doing anything. They decided he was resisting arrest. Paramedics were called to the scene and injected him with ketamine. (Once more: Elijah had been MINDING HIS OWN BUSINESS.) They took him to the hospital, and three days later he was dead.

Stories like Elijah’s are all too common. And all too often they involve Black victims.

Elijah McClain.

In policing, racism is not a bug. It’s a feature.

From the very beginning, policing was designed to keep Black people in check. Not Black criminals — Black people.

You can see this in the two texts that were used to establish the rules of policing, UC Berkeley African American Studies Professor Dr. Nikki Jones explains: Sir Robert Peel’s Principles of Law Enforcement of 1829 (you can tell that’s going to be bad for Black folks just by the name) and The Barbados Slave Code of 1661. (Ditto.)

“People still cite its emphasis on the relationship between policing and the public,” Jones told me about Peel’s Principles. “And what folks don’t understand is, at the time that Peel’s Principles were published, the public did not include Black people. And so the policing that Black people were subject to, enslaved Black people were subject to, that was dictated by the other founding document: The Barbados Slave Codes published in 1661.”

The Barbados Slave code says about what you would expect from a slave code; torture, maim, hunt, rape and execute were all perfectly fine for the White enslavers to do to the enslaved Africans. And most importantly, it wasn’t just kind of OK; the code specifies that the enslavers could commit all these humanitarian crimes with impunity. And you can draw a direct line from way back then to the modern era.

The US government already knows this: In 1968, an 11-member commission formed by President Lyndon B. Johnson’s administration released a document

called the Kerner Report that not only exposed the police as the tip of America’s racist spear, but pointed to systemic and cultural White racism as the driving force of that spear.

People march in the street to protest the death of Elijah McClain on July 25, 2020 in Aurora, Colorado. (Getty Images)

I see myself in Elijah McClain’s story. He described himself as “different.” I’m different too. Always have been. Elijah was a massage therapist who taught himself violin and then played it for stray cats. How could you think about hurting him? I want to hang out with him. There’s footage of him doing a silly dance into where he worked, quite literally dancing to the beat of his own drum. And I’m sure his mother fought to protect her son the same way that mine fought to protect me. I’m sure she knew full well — just like my mom did — that the way this country sees Black children, especially our young men and boys, puts a target on their backs from day one.

Why would you want to put more money into that?

Refund new possibilities

In the episode, my friend (and

“United Shades of America” alumnus) Pastor Michael McBride imagines a world where the police department is the same size as the fire department. He reminds us all, “Firefighters used to be called out to get cats out the tree. But then (cities) hired some pet control people. Because they understood that’s not a good use of that firefighters time.” Hard to argue with a man of the cloth when he makes such a good point.

A man looks over a memorial dedicated to Breonna Taylor in Louisville, Kentucky. (Photo by Brandon Bell/Getty Images)

That is the basic theory of the Defund movement: Why don’t we take some of the money and some of the responsibilities away from the police, and give the money and the responsibilities to people who are qualified to deal with those issues? People who aren’t trained to kill. People who aren’t trained to reach for any weapon as their main tool. People whose job descriptions are focused on help and de-escalation. If the pandemic has shown us anything — and it has shown us a lot — we need to build long-term, sustainable public safety and an economy that works for everyone. Whether you Google it or not, at least now you know. That’s “Defund 101.”

And versions of this are already happening around the country and in Oakland.

The Anti-Police Terror Project has set up a phone line that operates on Fridays and Saturdays for people who need help with issues surrounding mental health, domestic violence and substance abuse, but don’t want a police officer showing up. The billboards are up in Oakland in Black and Brown communities, where people are likely to have experienced police making those situations worse. It is just a start. But that’s what we need: A start.

![]()